On September 5, 2000, Owens Valley botanist and conservationist Mary DeDecker passed away. She was 91 years old and had lived in Independence with her husband, Paul, for 65 years.

Mary started the Bristlecone Chapter of the California Native Plant Society in 1982 and added immensely to our knowledge of the flora of eastern California. Mary also helped found the Owens Valley Committee (OVC) in 1983. As an outspoken conservationist with the OVC, she helped protect the Owens Valley from the Los Angeles Department of Water & Power’s (LADWP) environmentally damaging water exports and worked to protect Eureka Dunes from off-road vehicle (ORV) use.

Mary published numerous papers, wrote a book entitled “Mines of the Eastern Sierra,” (La Siesta Press, 1966 and 1991), taught courses, influenced conservation legislation and, most importantly, acted as an inspirational mentor for many aspiring botanists and conservationists.

Her knowledge was sought after by professional botanists and everyday plant lovers from the Owens Valley and statewide. Mary’s work had and will continue to have a significant effect on generations of people who value the beautiful desert areas of eastern California.

Mary Foster was delivered by her grandmother on the family farm in Oklahoma in 1909. Her family moved to southern California when she was eight years old. Mary credited her first encouragement in botany to her father, who helped her identify plants and grow them.

At high school in Van Nuys, Mary was elected a member of the elite Science Club, and the biology teacher put her in charge of students collecting plants for term projects. Although math and science were her favorite subjects, Mary didn’t get much encouragement to pursue an education in science.

Mary married Paul DeDecker in 1929. She attended U.C.L.A. and majored in art, another subject in which she excelled, but the depression put an end to her formal education. Their one car was needed by Paul for his job with LADWP, and as Mary recalled, “jobs were precious,” so Mary turned to her great love, botany, and began to study the plants around the San Fernando Valley where they lived.

After arriving in the Owens Valley in 1935 with her husband and their two young girls, Joan and Carol, Mary became very interested in the plants she saw in the Eastern Sierra and Northern Mojave Desert areas. The flora of the Eastern Sierra region was poorly known at that time, and Mary began teaching herself botany with the help of Willis Lynn Jepson’s Manual of the Flowering Plants of California.

In the 1950s she began sending specimens to Phillip Munz, who was working on the California Flora, at Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden. Dr. Munz gave Mary encouragement and guidance, and identified the plant specimens she sent him. Mary also collected and sent specimens to botanists specializing in various plant groups, and eventually built up an herbarium of some 6400 specimens in the garage of her home in Independence.

In addition, Mary made index cards for every species she encountered over the years with locations and other information. Bristlecone Chapter member Larry Blakely has scanned this collection of cards into a database that will be useful for future botanists working in our area. Before her death, Mary donated her herbarium collection to the herbarium at Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden.

Mary’s interest in the nearby desert mountains grew as she became involved with preservation of the Eureka Dunes, managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Not surprisingly, there was controversy over which roads should be open for ORV use. A “road” in the Last Chance Mountains from Saline Valley to Eureka Valley wound through a canyon and over dry falls.

Mary was concerned about the impact vehicles might have on Buddleja utahensis, a rare butterfly bush that occurs in this canyon. While she was there doing a survey of buddleja, she “picked a sprig of this strange bush that looked like a buckwheat and took it home.” She and Paul returned a month later on July 4 to collect it in flower, and were impressed with the dramatic view of this golden shrub growing all over the dark canyon walls. After John Thomas Howell inspected the specimens Mary sent him at the California Academy of Sciences, he told her she had a new genus.

He and James Reveal, a buckwheat expert from the University of Maryland, named it Dedeckera, in honor of Mary. Mary gave Dedeckera eurekensis the common name of July gold. Later, in 1984, Susan Cochrane of the California Department of Fish & Game succeeded in naming the canyon Dedeckera Canyon for the type locality of Dedeckera eurekensis.

In a 1985 interview, Mary remarked “…I was doubly pleased. I was, of course, very happy to have it named after my namesake, but I think it’s really a wonderful idea to have places named for plants because plants don’t really get enough recognition.” This discovery constituted the second new genus in California since 1949.

Mary also discovered the federally threatened Fish Slough milk-vetch, Astragalus lentiginosus var. piscinensis, in 1974, which is restricted to one desert wetland system north of Bishop. Dedecker’s clover, Trifolium macilentum var. dedeckerae, was also named for Mary. Other species first collected by Mary include what were known at the time as Astragalus ravenii, Lomatium inyoense, and Lupinus dedeckerae.

When the BLM initiated the Desert Study Program in 1970, Mary was the obvious choice to do a plant inventory for the northern Mojave Desert. BLM divided the Colorado Desert into three parts and the Mojave into four, with the northern portion consisting essentially of Inyo County east of Owens Valley and the southeastern tip of Mono County.

Mary called it “the most complex and least known part of [what] I consider the most interesting part of the California desert.” The project became much larger than anyone expected, and Mary recalled, “I found more plants here than they thought they had in the whole desert.” However, it turned out that the BLM wasn’t going to publish her inventory, and she asked CNPS if they would publish it. So with the help of some other botanists and reviewers and her trusty typewriter, Mary augmented her inventory, and Flora of the Northern Mojave Desert was published by CNPS in 1984.

Mary DeDecker’s persistence in defending the desert flora first began with her concern about the effects of water diversions by LADWP on plant communities in the Owens Valley. Mary was instrumental in providing important botanical information during the development of the landmark Inyo County Water Agreement, which in 1973 established environmental laws and provided mitigations for the environmental damage caused by excessive groundwater pumping and surface diversions.

Mary’s longtime friend and former Bristlecone Chapter president Betty Gilchrist remembers that “this fiery little lady with the soft firm voice was able to stand up to all manner of bureaucrats and politicians. Using her knowledge and experience to exert her influence, she made a difference.”

When asked by an interviewer what she would most like to be remembered for, Mary responded, “What I think would mean more to me than anything else is to feel that I have made some inroad in protecting Owens Valley in the water situation.” Mary’s tenure on the Owens Valley Committee, which helped craft key language in the water agreement, lasted more than a decade. Today species such as the rare alkali meadow endemic, Sidalcea covillei (Owens Valley checkerbloom), are recovering, and in some areas thriving, thanks to Mary’s repeated pressure on LADWP to recognize the importance of protecting rare plants.

“There is little doubt that Mary’s constant vigilance, knowledge and professional expertise had a positive influence –in Mary’s words– “in protecting Owens Valley in the water situation,”” says Betty Gilchrist.

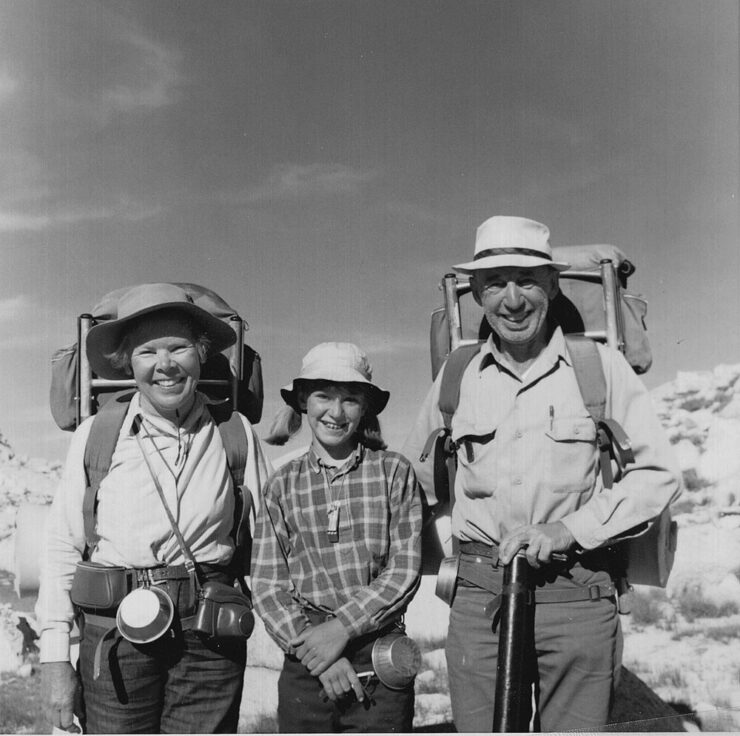

Betty recalls fondly field trips with the DeDeckers: “One of Mary’s natural talents and great interests was sharing her specialized knowledge, most often on well-planned and researched field trips. With plant list, magnifying glass, lunch and water, we would follow her anywhere, and her simple, charming manner drew many of us into a consuming interest in botany just for the joy of it. Field trips were often two days with overnight camp-outs. Who could forget those wonderful evening campfires and sharing of stories with Mary and Paul, establishing an easy camaraderie and long-lasting friendships?”

Anne Halford, BLM Botanist and a good friend of Mary’s, recalls two of her memorable field trips with Mary. “One outing many of us will remember is a trip into Cottonwood Basin led by Jim Morefield in the early 1990s. Mary, then in her mid-eighties, drove with vigor and great skill with her friend, Doris Fredendall, down through the steep and sandy grade that some of us were more than reluctant to attempt. That evening, after exploring the flora of Cottonwood Basin all day, Mary and Doris rolled out their sleeping pads and slept out under the stars with a very cold night to come.

The next morning, as all of us were complaining about the cold, we looked at Mary and Doris, who had just happily rolled up their sleeping bags and were ready to start another day of exploring. We again were humbled and amazed that despite the temperature, weather, or even a few sore joints, Mary would always be keen to embark on another botanical adventure.

“One of the last outings to Mary’s beloved Death Valley was during the incredible flower year of 1998. After a glorious picnic up Echo Canyon surrounded by the intoxicating fragrance of evening primrose, we ventured into the valley and watched Mary standing amidst a sea of desert gold with a smile as wide as the Death Valley horizon.”

Mary was named a CNPS Fellow in 1977 in recognition of her outstanding contributions to the botany of California native plants. Among her numerous awards is the 1988 CNPS Rare Plant Conservation Award. In honor of her long career promoting and protecting the plants of the Eastern Sierra region, Mary was given the Andrea Lawrence Lifetime Achievement Award by the local Sierra Club chapter in January, 1999.

Maybe someday we’ll be lucky enough to give a Mary DeDecker Lifetime Achievement Award to an outstanding individual who has contributed even half as much as she did. She will be missed by her many friends and fellow conservationists and botanists in the Owens Valley area and from all around the state.

–Stephen Ingram, Anne Halford, and Betty Gilchrist, Bristlecone Chapter, California Native Plant Society

Ed. note–Mary’s 1966 book Mines of the Eastern Sierra, originally issued by La Siesta Press, has now been reissued by Spotted Dog Press as Death Valley to Yosemite: Frontier Mining Camps & Ghost Towns.